Volcanic Ash Turns into Gems? Tips for a Sparkling “Bowl Sedimentation” Classroom Experiment

I’m Ken Kuwako, your science trainer. Every day is an experiment.

Unearthing a Time Capsule from the Dirt!

Observing volcanic ash can make students’ eyes light up. But just looking through a microscope won’t reveal the epic story hidden within each tiny particle. Many students think volcanic ash is just the residue of something that burned, but it’s actually a time capsule containing the history of our planet.

To make this experiment a success, you need a little bit of magic. It’s a simple but profound technique called “Wan-gake,” or “bowl rinsing.” With this one step, plain dirt transforms into a lesson that tells the story of Earth’s history spanning hundreds of thousands of years.

Wan-gake is an experimental method for separating heavy minerals from sand or volcanic ash using the buoyancy of water. The name comes from using a bowl-shaped container to separate materials by their specific gravity.

In this article, I’ll share some tips for the Wan-gake method, using volcanic ash from the Kanto Loam Layer and Sakurajima as examples. You’ll learn how to get results that will make students exclaim, “Wow, it looks like a treasure!”

Making Science Class a Special Experience

Wan-gake is an experimental method for separating heavy minerals from sand or volcanic ash using the buoyancy of water. The name comes from using a bowl-shaped container to separate materials by their specific gravity.

This experiment is more than just a simple observation. For students, it’s a treasure hunt to find hidden gems. They can see for themselves that volcanic ash isn’t just “burnt ash,” but that each particle is tangible proof of a volcanic eruption from the distant past.

What You’ll Need for the Class

Kanuma Soil: A type of weathered volcanic ash that resulted from the eruption of Mt. Akagi in Gunma Prefecture. It’s a slightly whitish, porous material with many small holes, making it light and well-draining.

|

|

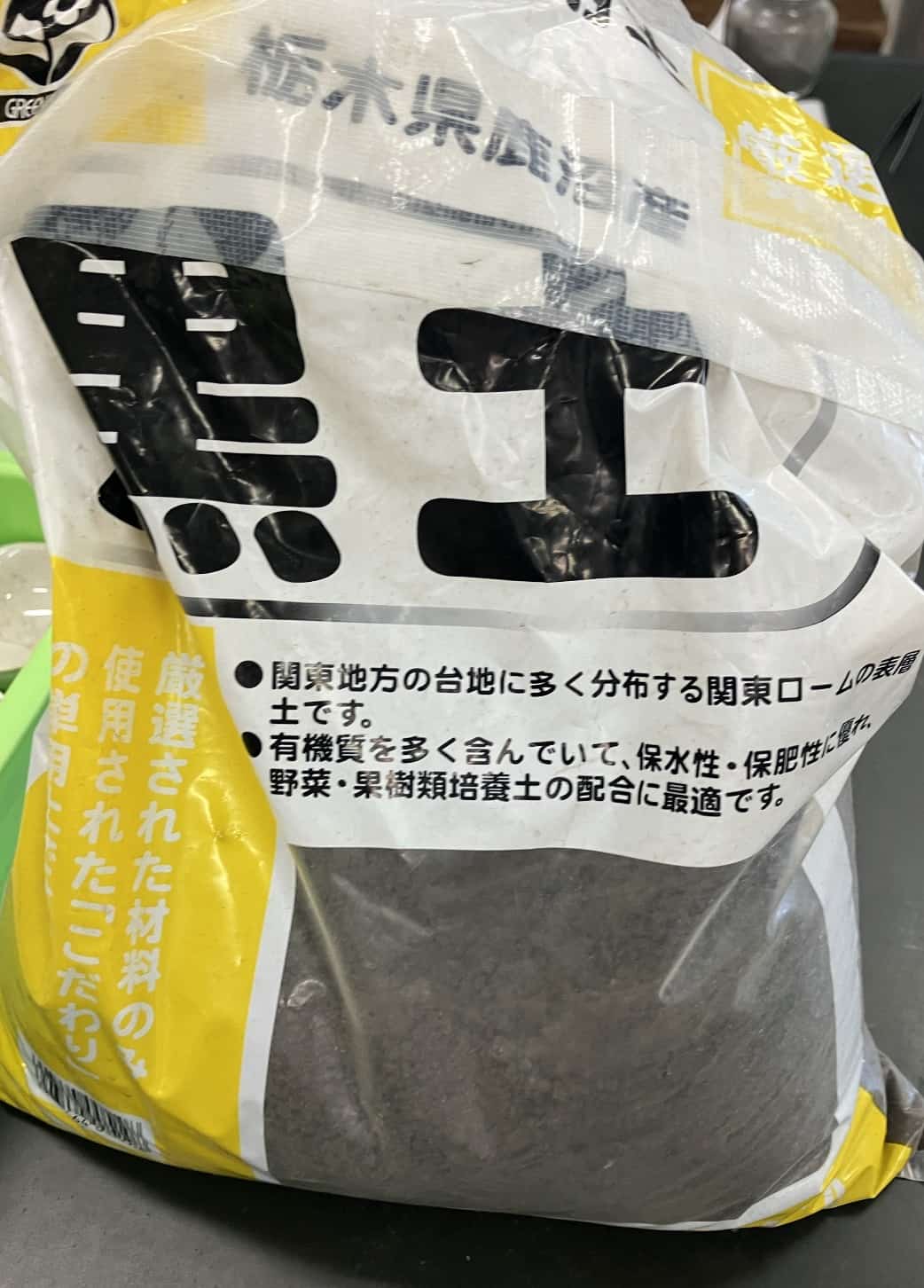

Akadama Soil: A soil derived from volcanic ash from the eruption of Mt. Nantai in Tochigi Prefecture. It’s characterized by its reddish-brown color and a slightly heavier, smoother-grained surface. Both soils are sold at garden centers.

Water

Petri dish

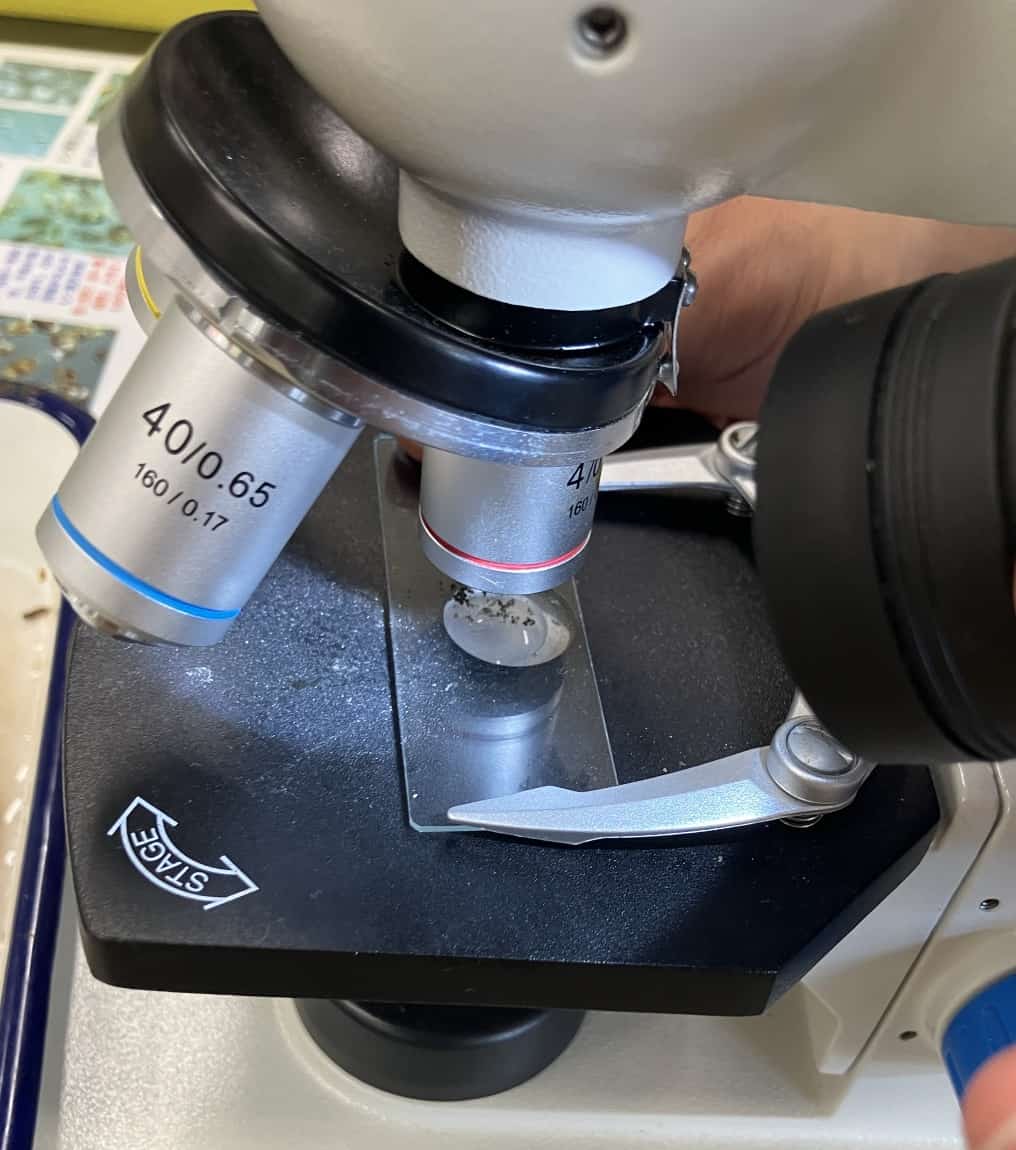

A stereo microscope (20x-40x magnification is good) or a regular microscope (40x)

Tweezers

A small brush

Paper towels or tissue (for drying)

Observing Volcanic Ash from Mt. Unzen-Fugen and Sakurajima

Now that you’re excited about the volcanoes hidden in potted plant soil, let’s observe volcanic ash from farther away. For this, I prepared volcanic ash from Mt. Unzen-Fugen and Sakurajima.

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Wan-gake Method

For this experiment, I used “Kanuma soil” from the Kanto Loam Layer, which you can find at a garden center, and Sakurajima volcanic ash, which I got separately.

Put the soil in a bowl and add a little water.

The key here is to gently crush and wash the dirt with the pad of your thumb. Rubbing it with your finger helps to separate the fine particles of clay and mud from the mineral grains. After crushing it a bit, add a little more water and pour the murky liquid into a separate tray. Be sure to instruct students to collect the murky water in a tray, as pouring it down the drain could clog the pipes. Repeat this process until the water is no longer cloudy.

Once the water is clear, transfer the remaining minerals onto a paper towel. Place another paper towel on top and gently press to absorb the excess water.

After the minerals are dry, place them on a slide and tap gently to spread them out.

The Difference a Good Rinse Makes

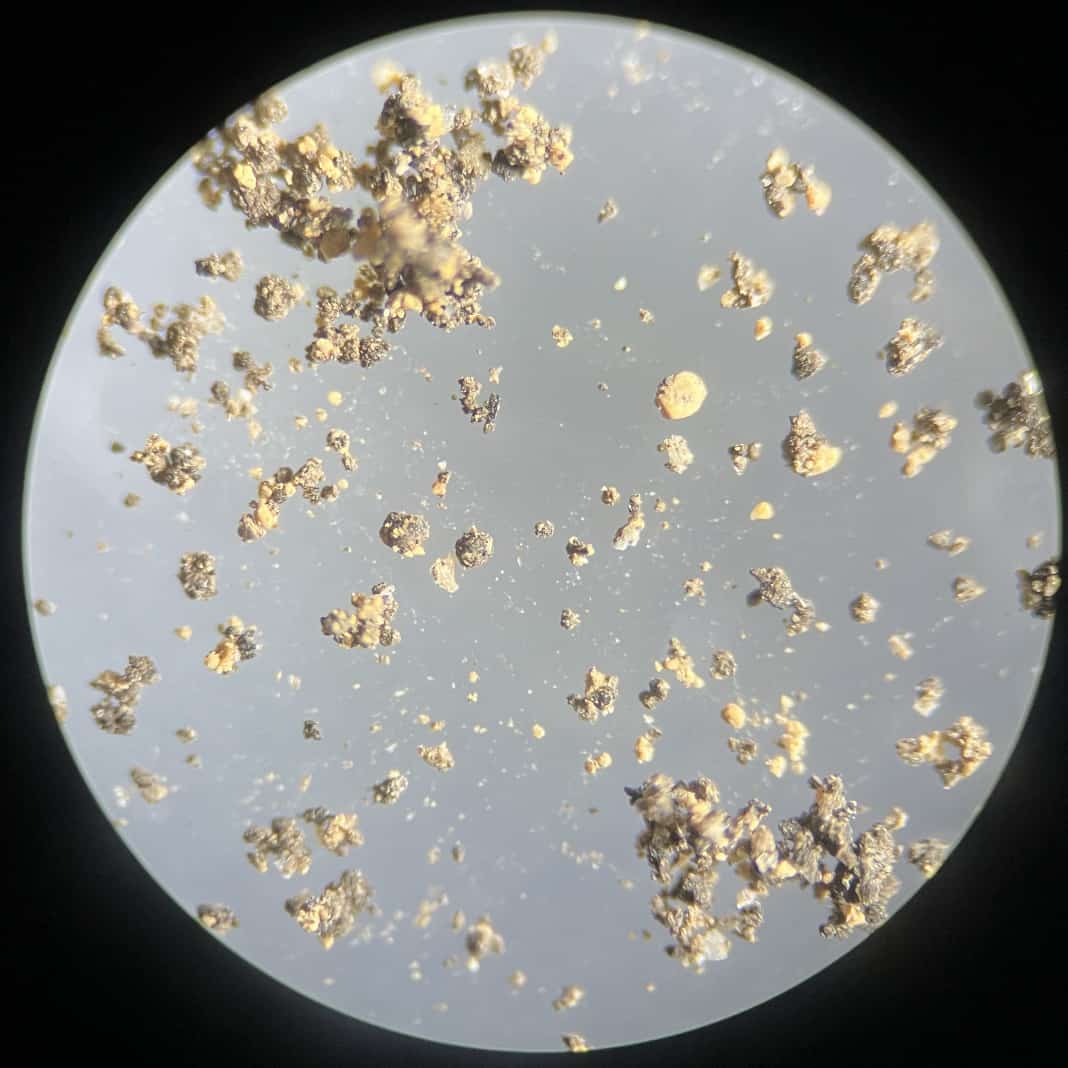

If the Wan-gake is not done properly, a layer of mud will remain, and the minerals won’t be clearly visible.

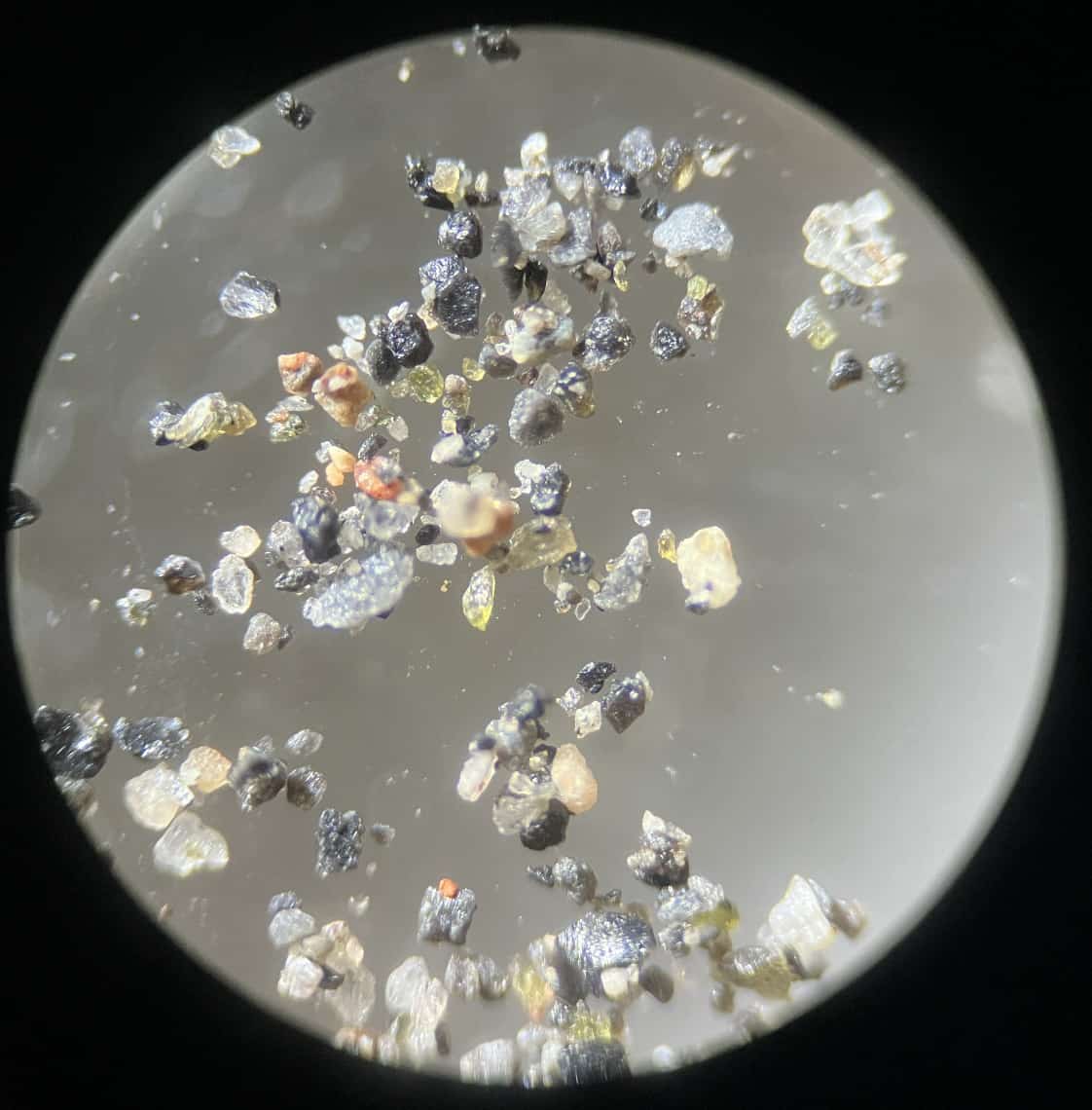

However, if you do it right, you can clearly observe the colorful minerals.

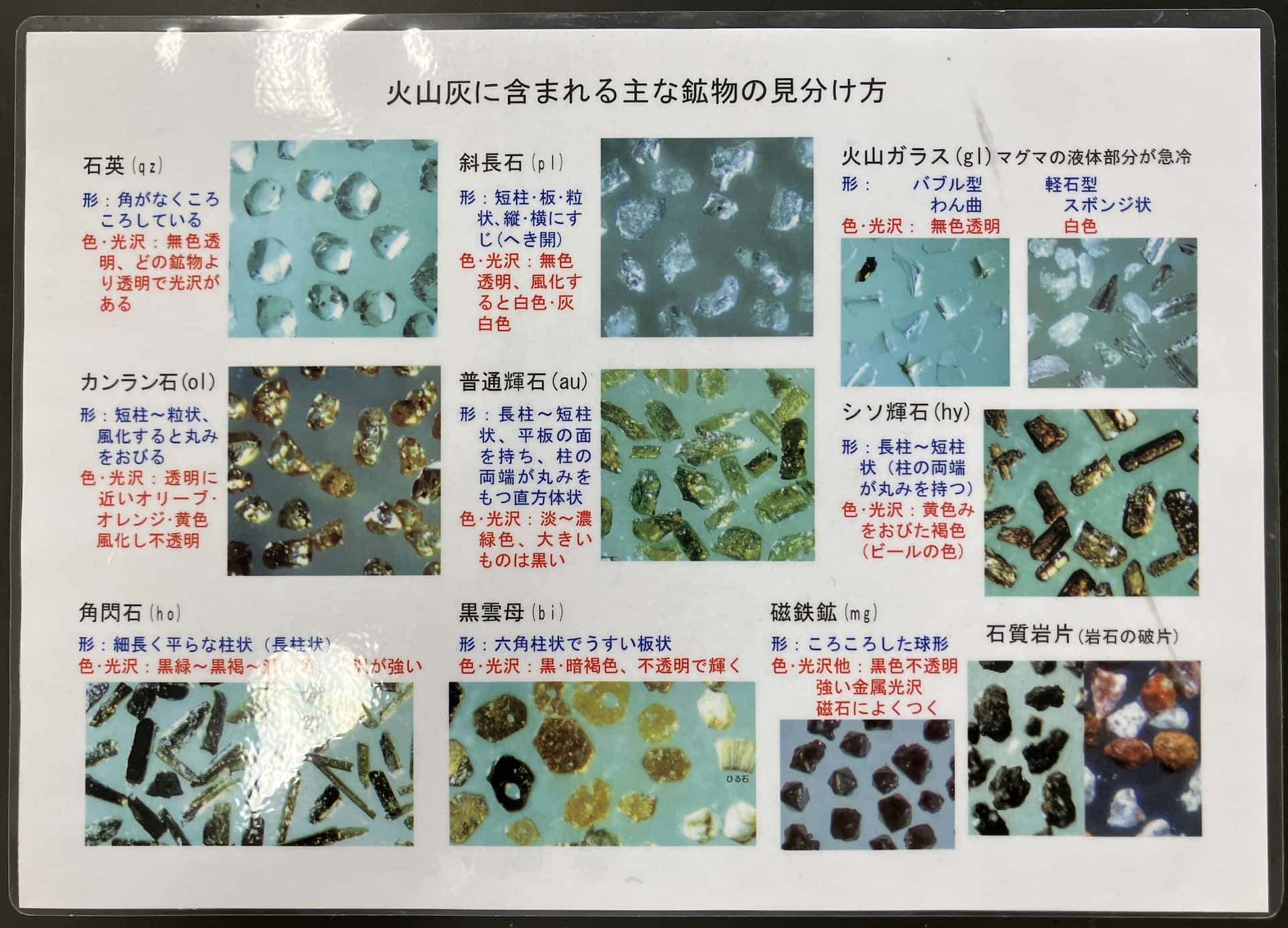

In the Kanto Loam Layer, you can see plagioclase in the center and quartz on the left.

Learning Earth’s Story from Sakurajima Ash

Volcanic ash from Sakurajima is known for having minerals that are even clearer than those found in the Kanto Loam Layer.

You can observe minerals of various colors and shapes—transparent, yellow, brown, black, and more.

These minerals are crystals that formed as the magma cooled. The differences in color, shape, and hardness are determined by the magma’s composition and cooling speed. For example, dark-colored mafic minerals (like amphibole and pyroxene) contain a lot of iron and magnesium, while white-colored felsic minerals (like quartz and plagioclase) are rich in silica.

Our Discoveries

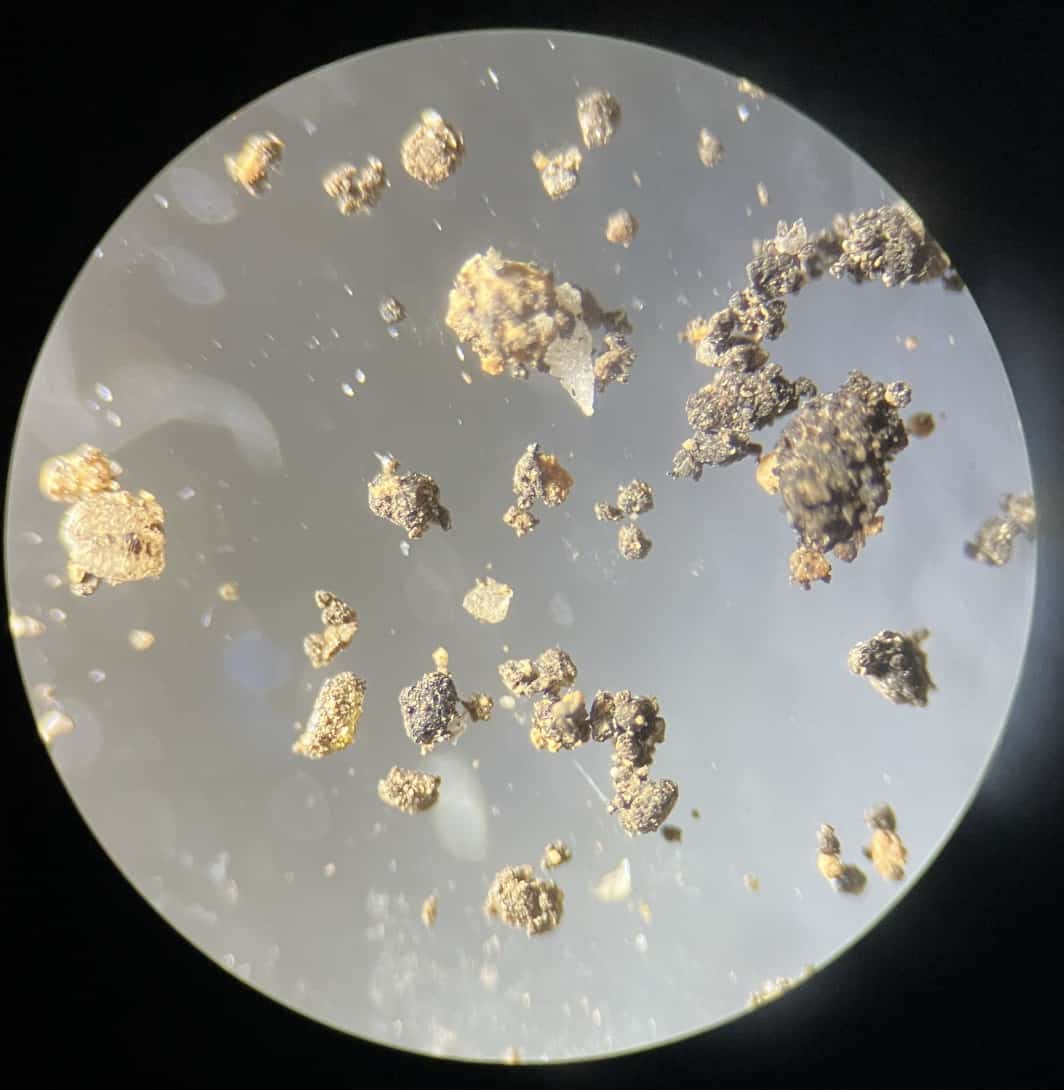

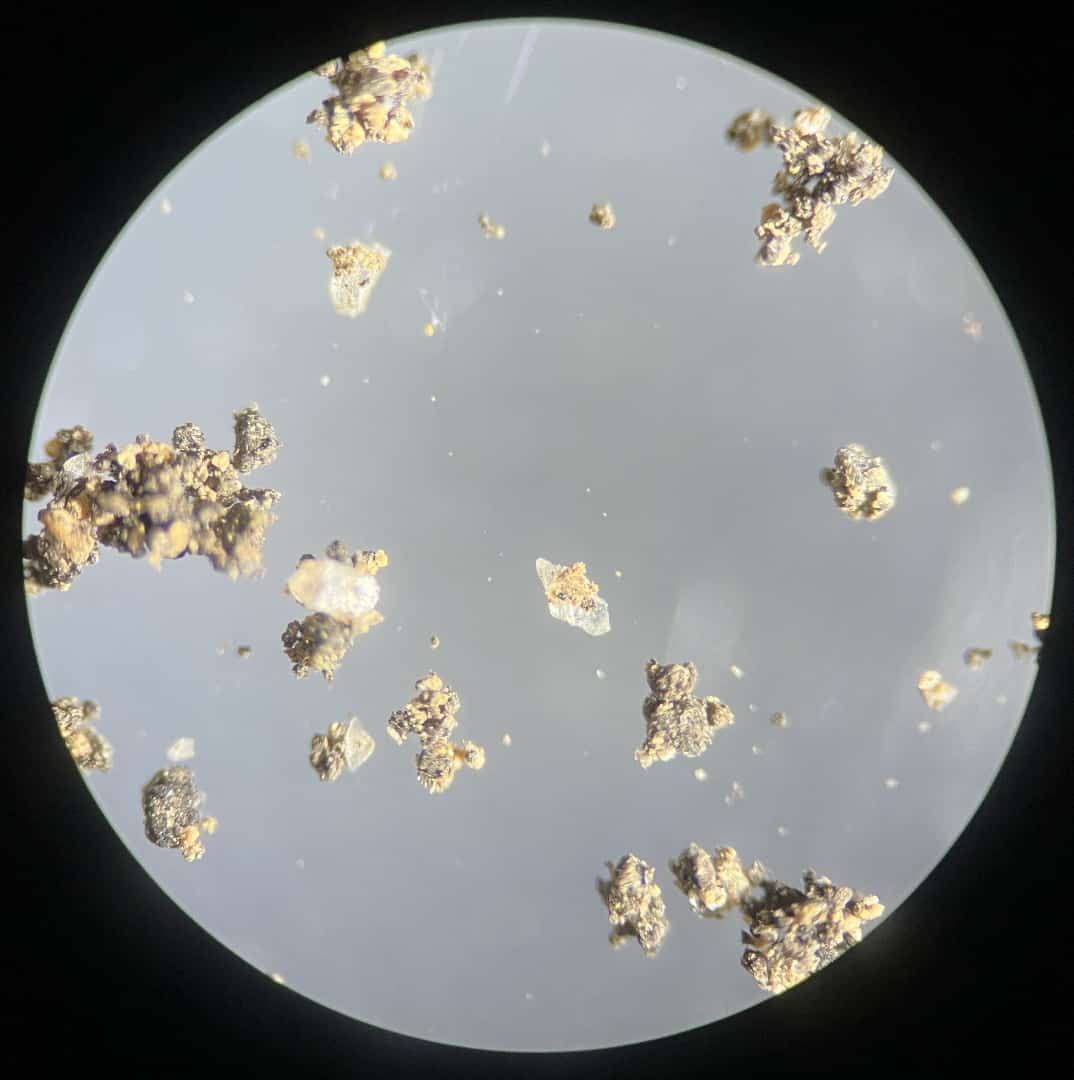

Here’s the Mt. Unzen-Fugen ash on the left and the Sakurajima ash on the right. The Unzen-Fugen ash was a white color, while the Sakurajima ash was blackish. This color difference shows that the magma composition and eruption style of the two volcanoes were different.

By showing students the differences in volcanic ash from different regions, you can grab their interest. You can also introduce terms like “mafic minerals” and “felsic minerals” while showing them the actual samples. From the color and shape of the volcanic ash particles, you can even expand the discussion to the type of eruption (e.g., explosive or effusive).

Using a stereo microscope for observation is quite rare in geology classes and is a perfect opportunity to nurture students’ appreciation for science as a visual subject. It only requires a little preparation, so be sure to give that stereo microscope in your science room a chance to shine!

![[商品価格に関しましては、リンクが作成された時点と現時点で情報が変更されている場合がございます。] [商品価格に関しまましては、リンクが作成された時点と現時点で情報が変更されている場合がございます。]](https://hbb.afl.rakuten.co.jp/hgb/2b71acab.9c66f40c.2b71acac.71d48030/?me_id=1216297&item_id=10000012&pc=https%3A%2F%2Fthumbnail.image.rakuten.co.jp%2F%400_mall%2Fheiwa%2Fcabinet%2F00529276%2Fheiwakanuma.jpg%3F_ex%3D240x240&s=240x240&t=picttext)